Code to allow OTA installation of alternative firmware on Sonoff devices, avoiding the need to connect to the serial port.

Source: mirko/SonOTA: Flashing Itead Sonoff devices with custom firmware via original OTA mechanism

Code to allow OTA installation of alternative firmware on Sonoff devices, avoiding the need to connect to the serial port.

Source: mirko/SonOTA: Flashing Itead Sonoff devices with custom firmware via original OTA mechanism

I recently discovered and purchased an inexpensive, unofficial WiFi-enabled AirPlay and DNLA audio receiver called the AirMobi iReceiver. I couldn’t find much information on the device, but for $12, I thought it was worth buying and trying.

It works reasonably well, but that’s not really why I bought it. I bought it with the intention of taking it apart and seeing what makes it tick. And now, having done that, I plan to hack it to run OpenWRT so I can secure it, customize it, and update the software.

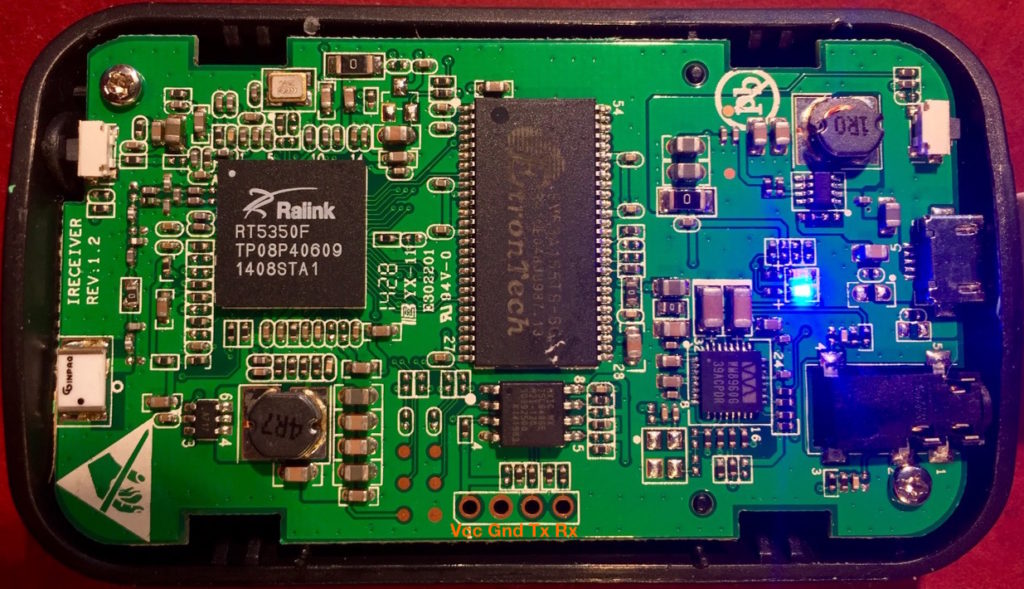

It is based on a Ralink RT5305T WiFi SoC which suggests to me that it is running linux, and probably has a serial console exposed via some test points on the mother board. I only found handful of candidates during my teardown. My guess was that the Tx and Rx lines were available on the unpopulated 4-pin header at the edge of the circuit board. From visual inspection I could tell that the second pin from the left was a ground pin. A little continuity probing with a multimeter suggested the first pin provided power, a fact confirmed when I check its voltage when I powered up the device.

I hooked a logic analyzer up to the other two pins to see which one toggled on and off at boot, but that was really overkill. I could have done just as well figuring out which one was pulled high when I powered up the device.

Once I had the pins worked out, I hooked up a TTL level USB/serial converter to my laptop, connected the ground pins and cross connected the Tx and Rx pins between the adapter and the board. Once I powered everything up, my screen started to fill with garbage. I guessed that 115.2Kbps was too fast, and tried 57.6Kbps instead. Bingo!

After booting up, I hit return and was presented with a login prompt. I tried the password for the webui and was pleased to find that it worked. I poked around the filesystem, looking at various config files, the various files for the web UI, and checking what binaries were installed on the system.

One of them is a telnet daemon (implemented as part of busybox). So, I started it, connected to the WiFi, and was able to log in over the network.

From there, I gathered more information. I was dissapointed that there wasn’t really anything like zip, or tar, or an ftp or ssh server that would make it easy to pull a bunch of files off at once, so I dumped the web UI files to the terminal one at a time and then saved them for further inspection.

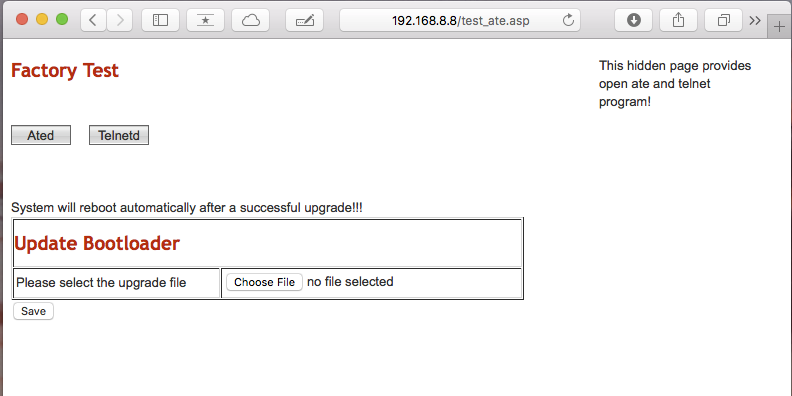

Hidden test_ate.asp page

Once I did, I found hidden functions in the firmware update page for uploading the bootloader over the webui. Exposing it required tweaking the page using web developer tools, which is kind of tedious. Then I hit the jackpot, I found an unlinked file called test_ate.asp. When loaded, it has a button to fire up the telnet daemon, making a command line available with just a WiFI connection, no serial console necessary. It also has an option to update the boot loader and a mysterious ATE function. This discovery made it easier to return and poke at the device at my leisure.

From what I learned in my poking and prodding, it appears to be based on the Ralink provided SDK with some modifications. With any luck, the modifications will be minor, and it will be easy to load an OpenWRT firmware over the webUI.

Before I do that though, I’ll need to take special care since this device doesn’t have an ethernet port, and so recovering from non-working firmware will be more difficult.

A lot of details follow…

I’ve ended up with five small, inexpensive ($7-15 each) routers, running OpenWrt and only really need two of them, so I’ve been thinking of ways to use the others. One of my ideas was to get an external USB DAC, install Shairport-Sync, and use it as an AirPlay receiver for my car stereo, eliminating the need to connect an audio cable to my phone, and avoiding the mediocre sound quality of Bluetooth audio. It hasn’t quite worked out that way though…

While looking for an inexpensive (>$20), compact USB DAC with reasonable quality, I discovered there were integrated commercial products that already do what I planned to do. I already knew there were Apple-approved MFi-certified devices, but they tended to be expensive. I discovered there were cheaper devices using Shairport, but they tended to start at $30+.

Damaged while trying to open the case.

With a little more digging though, I found a device called the iReceiver, from AirMobi that sells for as little as $12!!!. According to the scant marketing materials, it has a 24-bit Wolfson DAC. I was surprised I couldn’t find anyone who’d opened one up to see what was inside. I did find an Amazon review from someone complaining that the usb power connector had broken off on theirs, and the included photo showed it had a Ralink RT5350F WiFi SoC, which gave me hope that it would be hackable. So, I bought one.

Before opening it up, I tried it out. It works as promised. It defaults to broadcasting an unsecured WiFi network. Once connected, it shows up as an AirPlay receiver in iTunes, etc. From there, you can connect it to some powered speakers, select it and start playing music. The audio quality doesn’t suck (no obvious noise, clipping, or distortion), and in my limited use, there were fewer dropouts that I’m used to with Bluetooth.

Beyond that, there are various configuration options available through a browser based interface. There are no audio-related settings at all. Most of the settings are networking related. You can rename and secure the WiFi network with a password (good), WPS (bad) and by limited connections to specific devices by MAC address (meh). You can also connect to an existing network (good), and, optionally, extend it (meh). This seems like a good point to mention that it also works as a DNLA “renderer” (DNLA is a more open standard than AirPlay, making this useful to Windows and Linux devices, and Android phones with an appropriate app)

Of course, I didn’t buy it to use it with the stock firmware, so after trying it out, I opened it up to take a look inside. In the process, I managed to tear the translucent plastic that was affixed to the top of the case with adhesive. With the trim removed, it was easy to pry off the top, revealing the single PCB inside.

As I expected, it is based on the obsolete but inexpensive and popular Ralink RT5350F WiFi SoC which includes a CPU and 802.11n WiFi.

This is complimented by a modest, but sufficient 32MB of RAM and 8MB of flash memory to hold the firmware.

The other major component is a Wolfson WM8960 CODEC to provide the audio output. This chip debuted in 2006, and includes 24-bit stereo DAC and ADC converters supporting sample rates up to 48Khz, a 40mW headphone driver, and a 1W Class D speaker driver.

Despite being a 24-bit DAC, the specified SnR of 98dBS matches that of the 16-bit TI/Burr Brown PCM2705 DAC used in the original AirportExpress, rather than of a modern, premium 24-bit DAC used in more recent AirportExpress’s. Oh well. Good enough for my purposes. Most of what I’m playing is compressed AAC files derived from 16-bit sources, and, AirPlay only passes 16-bit anyway. Beyond that, the design of the rest of the circuitry matters, and I’m not qualified to analyze it, nor am I equipped or inclined to try and measure it.

Beyond that, I see two inductors on the board (one of which is cracked). My guess is that these are part of some small switch mode power supplies, perhaps one for the digital section, and the other for the analog. There are two small LEDs to indicate device status and two momentary switches, one to reset the device, and the other to trigger WPS. It looks like it uses a single ceramic chip antenna for the WiFi.

There are a few unused pads for components, eight test points (half seemingly to do with power) and four unused holes for pin headers that I suspect provide a serial console.

That’s really it for the hardware. I’ve already started poking more deeply into the software and investigating the suspected serial console, and I hope to have another post soon documenting what I found.

The Chaos Display is a sweet hack. Fredrik Hübinette wanted to use some individually addressable RGB LED light strings for a programmable holiday display, but he didn’t want to painstakingly place each light, so, he just wrapped the lights around his tree, and then wrote some software to calibrate the installation by lighting each light while recording it with a webcam. Additional software analyzed the video to produce a mapping of light ID to position.