This morning, I woke up with an itch, an itch to see a switch.

No, not that kind of switch, something bigger!

Nah, that’s not a switch…

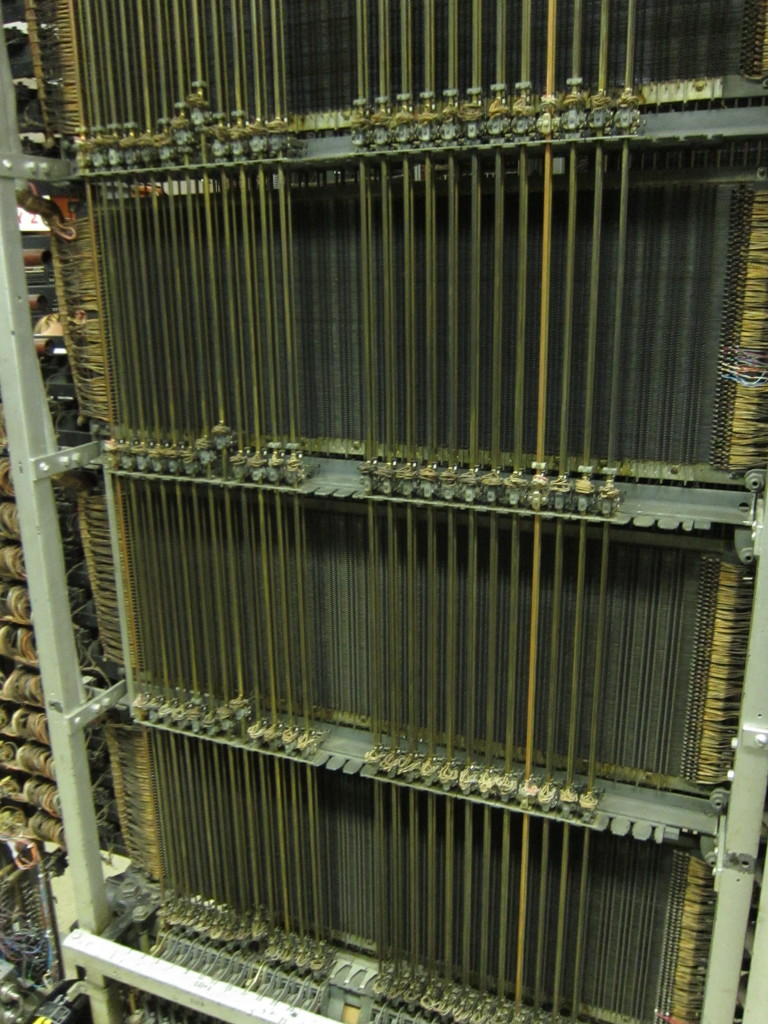

That’s a switch! Well, part of one.

It is part of a panel telephone switch, one of a number of operational telephone switches at The Herbert H Warrick Jr. Museum of Communications, a little known technological treasure trove in the Georgetown neighborhood of Seattle. The museum fills the top two floors of a Century Link central office building.

It is part of a panel telephone switch, one of a number of operational telephone switches at The Herbert H Warrick Jr. Museum of Communications, a little known technological treasure trove in the Georgetown neighborhood of Seattle. The museum fills the top two floors of a Century Link central office building.

The museum’s collection includes all manner of equipment and memorabilia from over a century of telephone history. The presentation of the collection is a bit uneven. There are carefully dated and labeled exhibits of phones and other equipment, along with display cases stuffed with lineman’s tools, but to me, that’s all secondary.

The best part of the museum is that it houses multiple generations of telephone exchange switching equipment, the sort of stuff that used to fill small buildings and connect thousands of homes to the telephone network. Much of it of it is operational, and interconnected, and attended by a staff of volunteers, many of them technicians and engineers retired after long careers with Ma Bell and her successors. They answer questions, give tours, and maintain the equipment.

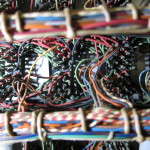

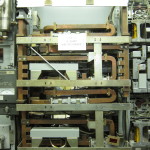

The automatic switching equipment spans almost a century. The oldest automatic switch is a panel switch that served the Rainier Valley. It was installed in the 1920s and served for over 50 years. Unlike that later automatic switches in the museum, which were made in a factory and then installed, the panel switch was assembled on site at the central office and moving it five decades required removing walls. They also have a #1 Crossbar Switch (#1XB) from the 1930s, and a #5 Crossbar (#5XB) from the 1950s. The panel and crossbar switches are all operational. Calls can be placed between lines serviced by the switches and you can hear the progress of the call set-up and tear-down sound across the racks as the various electromechanical parts do their thing. They also have a number of operational PBX systems, some old-time switchboards, some small Strowger step-by-step switches and a not yet operational #3ESS, a small variant of the first switches using transistorized logic for control.

The collection also includes inside plant, like power distribution equipment, outside plant, like cables, along with a variety of trunking and long-distance equipment, including equipment for carrying national network television broadcasts.

There is also test equipment spanning decades, and a nice cache of HAM radio equipment.

The museum was originally called the Vintage Telephone Equipment Museum when it was created in 1986 by Herbert H. Warrick Jr. Warrick was an engineering director at Pacific Northwest Bell, and started the museum with the company’s support to preserve generations of vintage telephone equipment that was being phased out in the transition to digital switching and transmission. More recently, it became affiliated with the Telecomunications History Group.

I’ve made many visits to the over the years, and each time, I learn something new. I recommend it to anyone with an affinity for technology, particularly communications and computing, but it should also interest anyone curious about industrial and economic history. I hope I’ve whetted your appetite.