I decided to buy a USB “power bank” or backup external battery to keep in my backpack to recharge my phone or iPad when I am away from the house.

I looked at lots of options over the course of a few months before I pulled the trigger. It was hard to make the decision because their seemed to be a big variance in capacity, price, and charging rates. What finally tipped me over the edge was finding a 10,000 mAh unit that could charge external devices at 2A and recharge at 2A for $17.99. Actually, the numbers associated with the model I purchased, (KMASHI 10,000 mAh) USB specs aren’t that unusual, but often times, the devices fall short of their claimed capacity. In this case though, there was a review by someone who’d done some testing and found that it pretty much hit the mark (though it did seem to fall short in the rate it charged USB devices).

When I received the product, I was a little disappointed. It worked as promised, and seemed solidly made, but It was bigger and heavier than I’d expected, and so I decided to crack it open to find out why.

It took some effort to get it open. I thought it might be glued shut, but with a little effort, I was able to persuade some of the latching tabs that held the case together to slip free by jamming something into a seam and working it around.

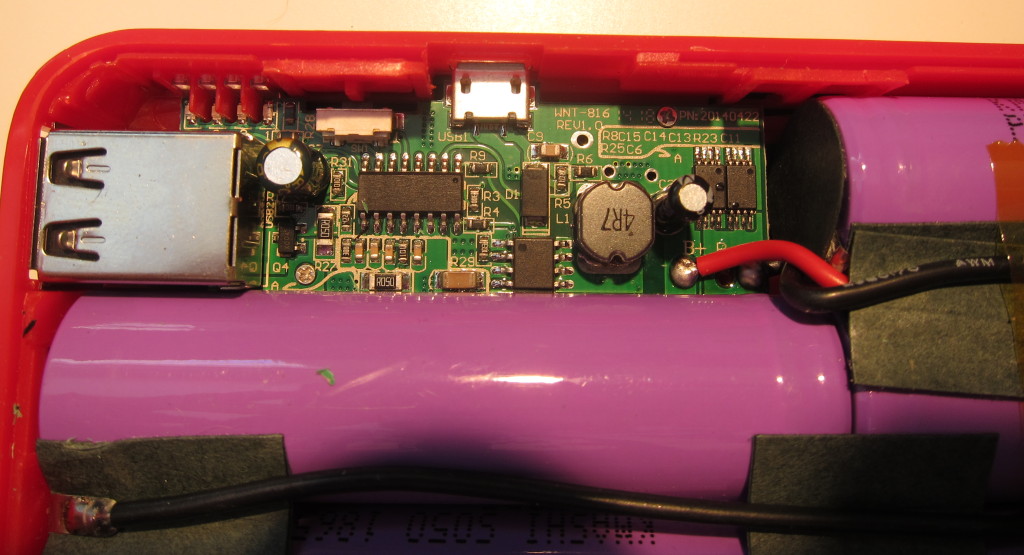

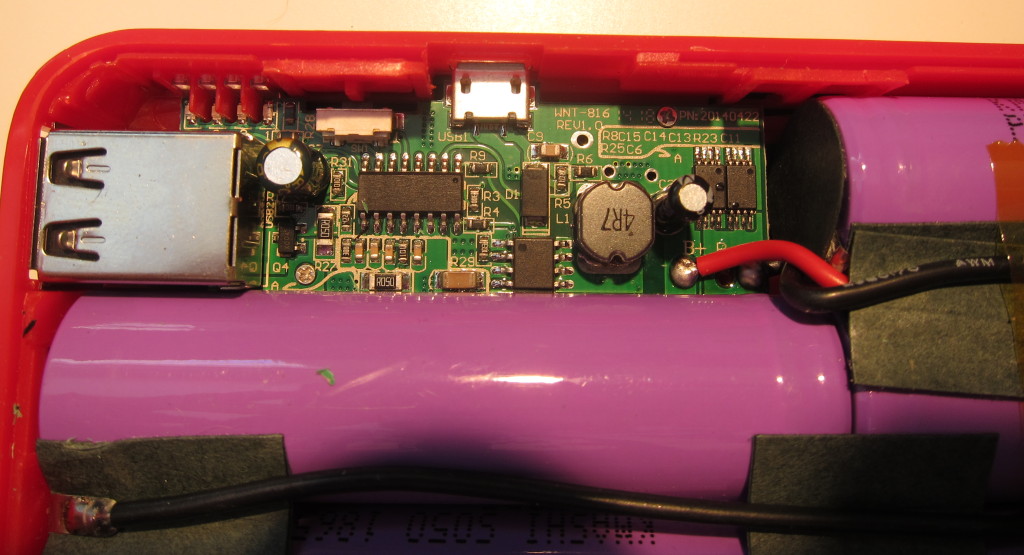

This is what I found inside. As you’d expect, a good portion of the volume is taken up by the batteries, five cylindrical 18650-sized lithium ion cells. This is the reason for the size and weight of the device. First off, the cylindrical cells don’t pack together as tightly as flat-pack pouch cells found in most phones, tablets, and higher end USB battery packs. Second, their steel walled container weighs more than the plastic membrane used on flat pouch cells.

This is what I found inside. As you’d expect, a good portion of the volume is taken up by the batteries, five cylindrical 18650-sized lithium ion cells. This is the reason for the size and weight of the device. First off, the cylindrical cells don’t pack together as tightly as flat-pack pouch cells found in most phones, tablets, and higher end USB battery packs. Second, their steel walled container weighs more than the plastic membrane used on flat pouch cells.

The bigger issue though is that there are five of them, which means that they must each have a capacity of only 2,000 mAh. That’s not much. 18650 cells (which stands for 18mm diameter, 65.mm length) are widely used for laptops, battery powered tools, and even Tesla automobiles. I pulled some 18650 cells out of ~5 year old laptop battery packs that are rated for 2,600 mAh and still deliver ~2,550 mAh. More recent laptops use cells with 3,000, 3,200, or perhaps even 3,400 mAh capacity, so it would be possible to build a power bank of equivalent capacity with four, or as few as three cells, with a corresponding reduction of weight and size.

On the other hand, those larger capacity cells from Panasonic, Samsung, Sony, and others, retail for $6-8/cell, and 2,600 mAh cells go for ~$3-3.50. I am sure these cells were much much cheaper.

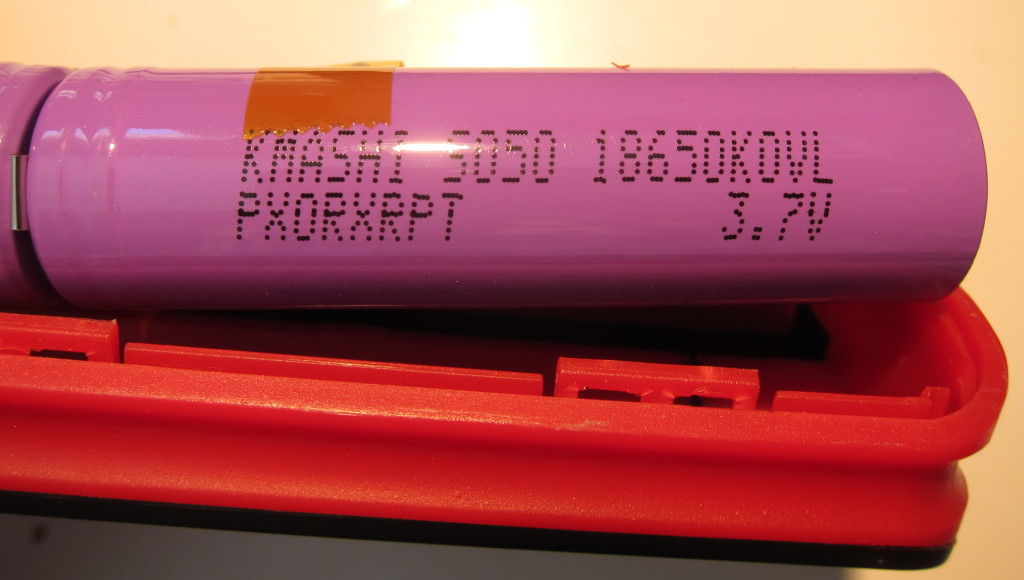

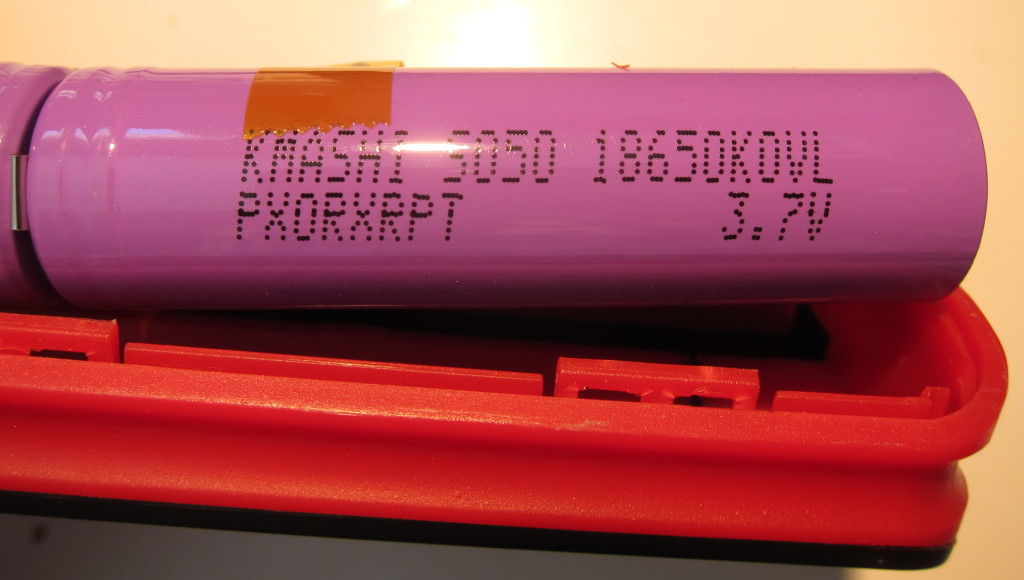

The cell wrappers are labeled “KMASHI SO50 18650KOVL PXORXRPT 3.7V,” This doesn’t give much of a clue as to the true origin of these cells. KMASHI doesn’t appear to be an actual battery manufacturer, that comes up in other contexts. 3.7V is the typical voltage for lithium ion cells, and 18650 is a common form factor, but searches for any of the terms on the label doesn’t produce useful results. I could cut the wrap off and see if there are any clues printed on the metal, but then I’d have to rewrap the cell, which would be a pain since they are all welded together.

So, who knows what kind of cells these are, they might even be reused used cells, for all I know.

This photo shows that the cells have been spot welded together in a parallel configuration, which is commonplace in multi-cell USB battery packs. I suspect the parallel approach is typically used for a few reasons. First, it should be more tolerant of lower quality cells than the series-configuration. Second, it should pose less of a risk of frying the USB device if the voltage regulation circuit is funky. Finally, it makes it easier to charge the pack off of a USB power adapter.

Looking at the end of these cells gives another hint that these may be reused cells. From my experience, raised bottoms are unusual on 18650 batteries, and others have reported that they are often used to hide the evidence of old welds on cells that have been pulled out of assembled battery packs.

If they are reused cells, that causes me some concern. If they are good quality cells from battery packs that just sat on the shelf (aka New Old Stock), then it would be a non-issue as I have obtained cells that way myself. If they’ve actually been used, or if they are from very old packs though, thats a problem, as they could fail prematurely, and failing lithium ion batteries can be dangerous.

For completeness, I give you the printed circuit board, which is labeled as “WNT-816 Rev 1.0” and “PN:20140422” on the top. I can’t say much about the components. The two largest chips appear to have been sanded to obscure their origins. There are two other chips that have their markings which read “FS8205A,” near as I can tell, they are used for managing the discharge of lithium-ion batteries.That, and the inductor is solid-core, unlike the many hollow-core inductors I’ve seen on the powerbank PCBs they sell on Fasttech.

On the bottom, it is labeled “wesemi-816.”

I reassembled it and I’ve used it since taking it apart. It works pretty much as expected. I’ll post an update in a few weeks once I get some stuff I ordered for testing USB power sources.